A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Outline |

| Influences |

| Research |

| Part of a series on |

| Universalism |

|---|

|

| Category |

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute,[1][2] but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning.[web 1] It may also refer to the attainment of insight in ultimate or hidden truths, and to human transformation supported by various practices and experiences.[web 2]

The term "mysticism" has Ancient Greek origins with various historically determined meanings.[web 1][web 2] Derived from the Greek word μύω múō, meaning "to close" or "to conceal",[web 2] mysticism referred to the biblical, liturgical, spiritual, and contemplative dimensions of early and medieval Christianity.[3] During the early modern period, the definition of mysticism grew to include a broad range of beliefs and ideologies related to "extraordinary experiences and states of mind."[4]

In modern times, "mysticism" has acquired a limited definition, with broad applications, as meaning the aim at the "union with the Absolute, the Infinite, or God".[web 1] This limited definition has been applied to a wide range of religious traditions and practices,[web 1] valuing "mystical experience" as a key element of mysticism.

Since the 1960s scholars have debated the merits of perennial and constructionist approaches in the scientific research of "mystical experiences".[5][6][7] The perennial position is now "largely dismissed by scholars",[8] most scholars using a contextualist approach, which considers the cultural and historical context.[9]

Etymology

"Mysticism" is derived from the Greek μύω, meaning "I conceal",[web 2] and its derivative μυστικός, mystikos, meaning 'an initiate'. The verb μύω has received a quite different meaning in the Greek language, where it is still in use. The primary meanings it has are "induct" and "initiate". Secondary meanings include "introduce", "make someone aware of something", "train", "familiarize", "give first experience of something".[web 3]

The related form of the verb μυέω (mueó or myéō) appears in the New Testament. As explained in Strong's Concordance, it properly means shutting the eyes and mouth to experience mystery. Its figurative meaning is to be initiated into the "mystery revelation". The meaning derives from the initiatory rites of the pagan mysteries.[web 4] Also appearing in the New Testament is the related noun μυστήριον (mustérion or mystḗrion), the root word of the English term "mystery". The term means "anything hidden", a mystery or secret, of which initiation is necessary. In the New Testament it reportedly takes the meaning of the counsels of God, once hidden but now revealed in the Gospel or some fact thereof, the Christian revelation generally, and/or particular truths or details of the Christian revelation.[web 5]

According to Thayer's Greek Lexicon, the term μυστήριον in classical Greek meant "a hidden thing", "secret". A particular meaning it took in Classical antiquity was a religious secret or religious secrets, confided only to the initiated and not to be communicated by them to ordinary mortals. In the Septuagint and the New Testament the meaning it took was that of a hidden purpose or counsel, a secret will. It is sometimes used for the hidden wills of humans, but is more often used for the hidden will of God. Elsewhere in the Bible it takes the meaning of the mystic or hidden sense of things. It is used for the secrets behind sayings, names, or behind images seen in visions and dreams. The Vulgate often translates the Greek term to the Latin sacramentum (sacrament).[web 5]

The related noun μύστης (mustis or mystis, singular) means the initiate, the person initiated to the mysteries.[web 5] According to Ana Jiménez San Cristobal in her study of Greco-Roman mysteries and Orphism, the singular form μύστης and the plural form μύσται are used in ancient Greek texts to mean the person or persons initiated to religious mysteries. These followers of mystery religions belonged to a select group, where access was only gained through an initiation. She finds that the terms were associated with the term βάκχος (Bacchus), which was used for a special class of initiates of the Orphic mysteries. The terms are first found connected in the writings of Heraclitus. Such initiates are identified in texts with the persons who have been purified and have performed certain rites. A passage of Cretans by Euripides seems to explain that the μύστης (initiate) who devotes himself to an ascetic life, renounces sexual activities, and avoids contact with the dead becomes known as βάκχος. Such initiates were believers in the god Dionysus Bacchus who took on the name of their god and sought an identification with their deity.[10]

Until the sixth century the practice of what is now called mysticism was referred to by the term contemplatio, c.q. theoria.[11] According to Johnston, "oth contemplation and mysticism speak of the eye of love which is looking at, gazing at, aware of divine realities."[11]

Definitions

According to Peter Moore, the term "mysticism" is "problematic but indispensable."[12] It is a generic term which joins together into one concept separate practices and ideas which developed separately,[12] According to Dupré, "mysticism" has been defined in many ways,[13] and Merkur notes that the definition, or meaning, of the term "mysticism" has changed through the ages.[web 1] Moore further notes that the term "mysticism" has become a popular label for "anything nebulous, esoteric, occult, or supernatural."[12]

Parsons warns that "what might at times seem to be a straightforward phenomenon exhibiting an unambiguous commonality has become, at least within the academic study of religion, opaque and controversial on multiple levels".[14] Because of its Christian overtones, and the lack of similar terms in other cultures, some scholars regard the term "mysticism" to be inadequate as a useful descriptive term.[12] Other scholars regard the term to be an inauthentic fabrication,[12][web 1] the "product of post-Enlightenment universalism."[12]

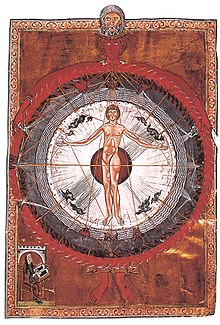

Union with the Divine or Absolute and mystical experience

Deriving from Neo-Platonism and Henosis, mysticism is popularly known as union with God or the Absolute.[1][2] In the 13th century the term unio mystica came to be used to refer to the "spiritual marriage," the ecstasy, or rapture, that was experienced when prayer was used "to contemplate both God’s omnipresence in the world and God in his essence."[web 1] In the 19th century, under the influence of Romanticism, this "union" was interpreted as a "religious experience," which provides certainty about God or a transcendental reality.[web 1][note 1]

An influential proponent of this understanding was William James (1842–1910), who stated that "in mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness."[16] William James popularized this use of the term "religious experience"[note 2] in his The Varieties of Religious Experience,[18][19][web 2] contributing to the interpretation of mysticism as a distinctive experience, comparable to sensory experiences.[20][web 2] Religious experiences belonged to the "personal religion,"[21] which he considered to be "more fundamental than either theology or ecclesiasticism".[21] He gave a Perennialist interpretation to religious experience, stating that this kind of experience is ultimately uniform in various traditions.[note 3]

McGinn notes that the term unio mystica, although it has Christian origins, is primarily a modern expression.[22] McGinn argues that "presence" is more accurate than "union", since not all mystics spoke of union with God, and since many visions and miracles were not necessarily related to union. He also argues that we should speak of "consciousness" of God's presence, rather than of "experience", since mystical activity is not simply about the sensation of God as an external object, but more broadly about "new ways of knowing and loving based on states of awareness in which God becomes present in our inner acts."[23]

However, the idea of "union" does not work in all contexts. For example, in Advaita Vedanta, there is only one reality (Brahman) and therefore nothing other than reality to unite with it—Brahman in each person (atman) has always in fact been identical to Brahman all along. Dan Merkur also notes that union with God or the Absolute is a too limited definition, since there are also traditions which aim not at a sense of unity, but of nothingness, such as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Meister Eckhart.[web 1] According to Merkur, Kabbala and Buddhism also emphasize nothingness.[web 1] Blakemore and Jennett note that "definitions of mysticism are often imprecise." They further note that this kind of interpretation and definition is a recent development which has become the standard definition and understanding.[web 6][note 4]

According to Gelman, "A unitive experience involves a phenomenological de-emphasis, blurring, or eradication of multiplicity, where the cognitive significance of the experience is deemed to lie precisely in that phenomenological feature".[web 2][note 5]

Religious ecstasies and interpretative context

Mysticism involves an explanatory context, which provides meaning for mystical and visionary experiences, and related experiences like trances. According to Dan Merkur, mysticism may relate to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness, and the ideas and explanations related to them.[web 1][note 6] Parsons stresses the importance of distinguishing between temporary experiences and mysticism as a process, which is embodied within a "religious matrix" of texts and practices.[26][note 7] Richard Jones does the same.[27] Peter Moore notes that mystical experience may also happen in a spontaneous and natural way, to people who are not committed to any religious tradition. These experiences are not necessarily interpreted in a religious framework.[28] Ann Taves asks by which processes experiences are set apart and deemed religious or mystical.[29]

Intuitive insight and enlightenment

Some authors emphasize that mystical experience involves intuitive understanding of the meaning of existence and of hidden truths, and the resolution of life problems. According to Larson, "mystical experience is an intuitive understanding and realization of the meaning of existence."[30][note 8] According to McClenon, mysticism is "the doctrine that special mental states or events allow an understanding of ultimate truths."[web 7][note 9] According to James R. Horne, mystical illumination is "a central visionary experience that results in the resolution of a personal or religious problem.[5][note 10]

According to Evelyn Underhill, illumination is a generic English term for the phenomenon of mysticism. The term illumination is derived from the Latin illuminatio, applied to Christian prayer in the 15th century.[31] Comparable Asian terms are bodhi, kensho and satori in Buddhism, commonly translated as "enlightenment", and vipassana, which all point to cognitive processes of intuition and comprehension. According to Wright, the use of the western word enlightenment is based on the supposed resemblance of bodhi with Aufklärung, the independent use of reason to gain insight into the true nature of our world, and there are more resemblances with Romanticism than with the Enlightenment: the emphasis on feeling, on intuitive insight, on a true essence beyond the world of appearances.[32]

Spiritual life and re-formation

Other authors point out that mysticism involves more than "mystical experience." According to Gellmann, the ultimate goal of mysticism is human transformation, not just experiencing mystical or visionary states.[web 2][note 13][note 14] According to McGinn, personal transformation is the essential criterion to determine the authenticity of Christian mysticism.[23][note 15]

History of the term

Hellenistic world

In the Hellenistic world, 'mystical' referred to "secret" religious rituals like the Eleusinian Mysteries.[web 2] The use of the word lacked any direct references to the transcendental.[14] A "mystikos" was an initiate of a mystery religion.

Early Christianity - theoria (contemplation)

In early Christianity the term "mystikos" referred to three dimensions, which soon became intertwined, namely the biblical, the liturgical and the spiritual or contemplative.[3] The biblical dimension refers to "hidden" or allegorical interpretations of Scriptures.[web 2][3] The liturgical dimension refers to the liturgical mystery of the Eucharist, the presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[web 2][3] The third dimension is the contemplative or experiential knowledge of God.[3]

Until the sixth century, the Greek term theoria, meaning "contemplation" in Latin, was used for the mystical interpretation of the Bible.[11] and the vision of God. The link between mysticism and the vision of the Divine was introduced by the early Church Fathers, who used the term as an adjective, as in mystical theology and mystical contemplation.[14]

Theoria enabled the Fathers to perceive depths of meaning in the biblical writings that escape a purely scientific or empirical approach to interpretation.[36] The Antiochene Fathers, in particular, saw in every passage of Scripture a double meaning, both literal and spiritual.[37]

Later, theoria or contemplation came to be distinguished from intellectual life, leading to the identification of θεωρία or contemplatio with a form of prayer[38] distinguished from discursive meditation in both East[39] and West.[40]

Medieval meaning

This threefold meaning of "mystical" continued in the Middle Ages.[3] According to Dan Merkur, the term unio mystica came into use in the 13th century as a synonym for the "spiritual marriage," the ecstasy, or rapture, that was experienced when prayer was used "to contemplate both God’s omnipresence in the world and God in his essence."[web 1] Under the influence of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite the mystical theology came to denote the investigation of the allegorical truth of the Bible,[3] and "the spiritual awareness of the ineffable Absolute beyond the theology of divine names."[41] Pseudo-Dionysius' Apophatic theology, or "negative theology", exerted a great influence on medieval monastic religiosity, although it was mostly a male religiosity, since women were not allowed to study.[42] It was influenced by Neo-Platonism, and very influential in Eastern Orthodox Christian theology. In western Christianity it was a counter-current to the prevailing Cataphatic theology or "positive theology". It is best known nowadays in the western world from Meister Eckhart and John of the Cross.

Early modern meaning

In the sixteenth and seventeenth century mysticism came to be used as a substantive.[14] This shift was linked to a new discourse,[14] in which science and religion were separated.[43]

Luther dismissed the allegorical interpretation of the bible, and condemned Mystical theology, which he saw as more Platonic than Christian.[44] "The mystical", as the search for the hidden meaning of texts, became secularised, and also associated with literature, as opposed to science and prose.[45]

Science was also distinguished from religion. By the middle of the 17th century, "the mystical" is increasingly applied exclusively to the religious realm, separating religion and "natural philosophy" as two distinct approaches to the discovery of the hidden meaning of the universe.[46] The traditional hagiographies and writings of the saints became designated as "mystical", shifting from the virtues and miracles to extraordinary experiences and states of mind, thereby creating a newly coined "mystical tradition".[4] A new understanding developed of the Divine as residing within human, an essence beyond the varieties of religious expressions.[14]

Contemporary meaning

The 19th century saw a growing emphasis on individual experience, as a defense against the growing rationalism of western society.[19][web 1] The meaning of mysticism was considerably narrowed:[web 1]

The competition between the perspectives of theology and science resulted in a compromise in which most varieties of what had traditionally been called mysticism were dismissed as merely psychological phenomena and only one variety, which aimed at union with the Absolute, the Infinite, or God—and thereby the perception of its essential unity or oneness—was claimed to be genuinely mystical. The historical evidence, however, does not support such a narrow conception of mysticism.[web 1]

Under the influence of Perennialism, which was popularised in both the west and the east by Unitarianism, Transcendentalists and Theosophy, mysticism has been applied to a broad spectrum of religious traditions, in which all sorts of esotericism and religious traditions and practices are joined together.[47][48][19] The term mysticism was extended to comparable phenomena in non-Christian religions,[web 1] where it influenced Hindu and Buddhist responses to colonialism, resulting in Neo-Vedanta and Buddhist modernism.[48][49]

In the contemporary usage "mysticism" has become an umbrella term for all sorts of non-rational world views,[50] parapsychology and pseudoscience.[51][52][53][54] William Harmless even states that mysticism has become "a catch-all for religious weirdness".[55] Within the academic study of religion the apparent "unambiguous commonality" has become "opaque and controversial".[14] The term "mysticism" is being used in different ways in different traditions.[14] Some call to attention the conflation of mysticism and linked terms, such as spirituality and esotericism, and point at the differences between various traditions.[56]

Variations of mysticismedit

Based on various definitions of mysticism, namely mysticism as an experience of union or nothingness, mysticism as any kind of an altered state of consciousness which is attributed in a religious way, mysticism as "enlightenment" or insight, and mysticism as a way of transformation, "mysticism" can be found in many cultures and religious traditions, both in folk religion and organized religion. These traditions include practices to induce religious or mystical experiences, but also ethical standards and practices to enhance self-control and integrate the mystical experience into daily life.

Dan Merkur notes, though, that mystical practices are often separated from daily religious practices, and restricted to "religious specialists like monastics, priests, and other renunciates.[web 1]

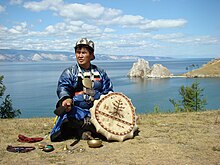

Shamanismedit

According to Dan Merkur, shamanism may be regarded as a form of mysticism, in which the world of spirits is accessed through religious ecstasy.[web 1] According to Mircea Eliade shamanism is a "technique of religious ecstasy."[57]

Shamanism involves a practitioner reaching an altered state of consciousness in order to perceive and interact with spirits, and channel transcendental energies into this world.[58] A shaman is a person regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into trance during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.[59]

Neoshamanism refers to "new"' forms of shamanism, or methods of seeking visions or healing, typically practiced in Western countries. Neoshamanism comprises an eclectic range of beliefs and practices that involve attempts to attain altered states and communicate with a spirit world, and is associated with New Age practices.[60][61]

Western mysticismedit

Mystery religionsedit

The Eleusinian Mysteries, (Greek: Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια) were annual initiation ceremonies in the cults of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone, held in secret at Eleusis (near Athens) in ancient Greece.[62] The mysteries began in about 1600 B.C. in the Mycenean period and continued for two thousand years, becoming a major festival during the Hellenic era, and later spreading to Rome.[63] Numerous scholars have proposed that the power of the Eleusinian Mysteries came from the kykeon's functioning as an entheogen.[64]

Christian mysticismedit

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|