A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Owl Temporal range: Late Paleocene to recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Telluraves |

| Order: | Strigiformes Wagler, 1830 |

| Families | |

|

Strigidae | |

| |

| range of all species of owls, combined | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Strigidae sensu Sibley & Ahlquist | |

Owls are birds from the order Strigiformes[1] (/ˈstrɪdʒəfɔːrmiːz/), which includes over 200 species of mostly solitary and nocturnal birds of prey typified by an upright stance, a large, broad head, binocular vision, binaural hearing, sharp talons, and feathers adapted for silent flight. Exceptions include the diurnal northern hawk-owl and the gregarious burrowing owl.

Owls are divided into two families: the true (or typical) owl family, Strigidae, and the barn-owl family, Tytonidae.[2] Owls hunt mostly small mammals, insects, and other birds, although a few species specialize in hunting fish. They are found in all regions of the Earth except the polar ice caps and some remote islands.

A group of owls is called a "parliament".[3]

Anatomy

Owls possess large, forward-facing eyes and ear-holes, a hawk-like beak, a flat face, and usually a conspicuous circle of feathers, a facial disc, around each eye. The feathers making up this disc can be adjusted to sharply focus sounds from varying distances onto the owls' asymmetrically placed ear cavities. Most birds of prey have eyes on the sides of their heads, but the stereoscopic nature of the owl's forward-facing eyes permits the greater sense of depth perception necessary for low-light hunting. Owls have binocular vision, but they must rotate their entire heads to change the focus of their view because, like most birds, their eyes are fixed in their sockets. Owls are farsighted and cannot clearly see anything nearer than a few centimetres of their eyes. Caught prey can be felt by owls with the use of filoplumes—hairlike feathers on the beak and feet that act as "feelers". Their far vision, particularly in low light, is exceptionally good.

Owls can rotate their heads and necks as much as 270°. Owls have 14 neck vertebrae — humans have only seven — and their vertebral circulatory systems are adapted to allow them to rotate their heads without cutting off blood to the brain. Specifically, the foramina in their vertebrae through which the vertebral arteries pass are about 10 times the diameter of the artery, instead of about the same size as the artery, as is the case in humans; the vertebral arteries enter the cervical vertebrae higher than in other birds, giving the vessels some slack, and the carotid arteries unite in a very large anastomosis or junction, the largest of any bird's, preventing blood supply from being cut off while they rotate their necks. Other anastomoses between the carotid and vertebral arteries support this effect.[4][5]

The smallest owl—weighing as little as 31 g (1+3⁄32 oz) and measuring some 13.5 cm (5+1⁄4 in)—is the elf owl (Micrathene whitneyi).[6] Around the same diminutive length, although slightly heavier, are the lesser known long-whiskered owlet (Xenoglaux loweryi) and Tamaulipas pygmy owl (Glaucidium sanchezi).[6] The largest owls are two similarly sized eagle owls; the Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) and Blakiston's fish owl (Bubo blakistoni). The largest females of these species are 71 cm (28 in) long, have a 190 cm (75 in) wing span, and weigh 4.2 kg (9+1⁄4 lb).[6][7][8][9][10]

Different species of owls produce different sounds; this distribution of calls aids owls in finding mates or announcing their presence to potential competitors, and also aids ornithologists and birders in locating these birds and distinguishing species. As noted above, their facial discs help owls to funnel the sound of prey to their ears. In many species, these discs are placed asymmetrically, for better directional location.

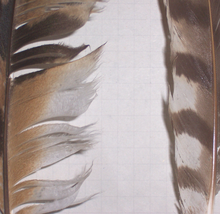

Owl plumage is generally cryptic, although several species have facial and head markings, including face masks, ear tufts, and brightly colored irises. These markings are generally more common in species inhabiting open habitats, and are thought to be used in signaling with other owls in low-light conditions.[11]

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is a physical difference between males and females of a species. Female owls are typically larger than the males.[12] The degree of size dimorphism varies across multiple populations and species, and is measured through various traits, such as wing span and body mass.[12]

One theory suggests that selection has led males to be smaller because it allows them to be efficient foragers. The ability to obtain more food is advantageous during breeding season. In some species, female owls stay at their nest with their eggs while it is the responsibility of the male to bring back food to the nest.[13] If food is scarce, the male first feeds himself before feeding the female.[14] Small birds, which are agile, are an important source of food for owls. Male burrowing owls have been observed to have longer wing chords than females, despite being smaller than females.[14] Furthermore, owls have been observed to be roughly the same size as their prey.[14] This has also been observed in other predatory birds,[13] which suggests that owls with smaller bodies and long wing chords have been selected for because of the increased agility and speed that allows them to catch their prey.[citation needed]

Another popular theory suggests that females have not been selected to be smaller like male owls because of their sexual roles. In many species, female owls may not leave the nest. Therefore, females may have a larger mass to allow them to go for a longer period of time without starving. For example, one hypothesized sexual role is that larger females are more capable of dismembering prey and feeding it to their young, hence female owls are larger than their male counterparts.[12]

A different theory suggests that the size difference between male and females is due to sexual selection: since large females can choose their mate and may violently reject a male's sexual advances, smaller male owls that have the ability to escape unreceptive females are more likely to have been selected.[14]

If the character is stable, there can be different optimums for both sexes. Selection operates on both sexes at the same time; therefore it is necessary to explain not only why one of the sexes is relatively bigger, but also why the other sex is smaller.[15] If owls are still evolving toward smaller bodies and longer wing chords, according to V. Geodakyan's Evolutionary Theory of Sex, males should be more advanced on these characters. Males are viewed as an evolutionary vanguard of a population, and sexual dimorphism on the character, as an evolutionary "distance" between the sexes. "Phylogenetic rule of sexual dimorphism" states that if there exists a sexual dimorphism on any character, then the evolution of this trait goes from the female form toward the male one.[16]

Hunting adaptations

All owls are carnivorous birds of prey and live on diets of insects, small rodents and lagomorphs. Some owls are also specifically adapted to hunt fish. They are very adept in hunting in their respective environments. Since owls can be found in nearly all parts of the world and across a multitude of ecosystems, their hunting skills and characteristics vary slightly from species to species, though most characteristics are shared among all species.[17]

Flight and feathers

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Most owls share an innate ability to fly almost silently and also more slowly in comparison to other birds of prey. Most owls live a mainly nocturnal lifestyle and being able to fly without making any noise gives them a strong advantage over prey alert to the slightest sound in the night. A silent, slow flight is not as necessary for diurnal and crepuscular owls given that prey can usually see an owl approaching. Owls' feathers are generally larger than the average birds' feathers, have fewer radiates, longer pennulum, and achieve smooth edges with different rachis structures.[18] Serrated edges along the owl's remiges bring the flapping of the wing down to a nearly silent mechanism. The serrations are more likely reducing aerodynamic disturbances, rather than simply reducing noise.[19] The surface of the flight feathers is covered with a velvety structure that absorbs the sound of the wing moving. These unique structures reduce noise frequencies above 2 kHz,[20] making the sound level emitted drop below the typical hearing spectrum of the owl's usual prey[20][21] and also within the owl's own best hearing range.[22][23] This optimizes the owl's ability to silently fly to capture prey without the prey hearing the owl first as it flies, and to hear any noise the prey makes. It also allows the owl to monitor the sound output from its flight pattern.

The disadvantage of such feather adaptations for barn owls is that their feathers are not waterproof.[24] The adaptations mean that barn owls do not use the uropygial gland, informally the "preen" or "oil" gland, as most birds do, to spread oils across their plumage through preening.[25] This makes them highly vulnerable to heavy rain when they are unable to hunt.[26] Historically, they would switch to hunting indoors in wet weather, using barns and other agricultural buildings, but the decline in the numbers of these structures in the 20th and 21st centuries has reduced such opportunities.[24] The lack of waterproofing means that barn owls are also susceptible to drowning, in drinking troughs and other structures with smooth sides. The Barn Owl Trust provides advice on how this can be mitigated, by the installation of floats.[27]

Vision

Eyesight is a particular characteristic of the owl that aids in nocturnal prey capture. Owls are part of a small group of birds that live nocturnally, but do not use echolocation to guide them in flight in low-light situations. Owls are known for their disproportionally large eyes in comparison to their skulls. An apparent consequence of the evolution of an absolutely large eye in a relatively small skull is that the eye of the owl has become tubular in shape. This shape is found in other so-called nocturnal eyes, such as the eyes of strepsirrhine primates and bathypelagic fishes.[28] Since the eyes are fixed into these sclerotic tubes, they are unable to move the eyes in any direction.[29] Instead of moving their eyes, owls swivel their heads to view their surroundings. Owls' heads are capable of swiveling through an angle of roughly 270°, easily enabling them to see behind them without relocating the torso.[29] This ability keeps bodily movement at a minimum, thus reduces the amount of sound the owl makes as it waits for its prey. Owls are regarded as having the most frontally placed eyes among all avian groups, which gives them some of the largest binocular fields of vision. Owls are farsighted and cannot focus on objects within a few centimetres of their eyes.[28][30] These mechanisms are only able to function due to the large-sized retinal image.[31] Thus, the primary nocturnal function in the vision of the owl is due to its large posterior nodal distance; retinal image brightness is only maximized to the owl within secondary neural functions.[31] These attributes of the owl cause its nocturnal eyesight to be far superior to that of its average prey.[31]

Hearing

Owls exhibit specialized hearing functions and ear shapes that also aid in hunting. They are noted for asymmetrical ear placements on the skull in some genera. Owls can have either internal or external ears, both of which are asymmetrical. Asymmetry has not been reported to extend to the middle or internal ear of the owl. Asymmetrical ear placement on the skull allows the owl to pinpoint the location of its prey. This is especially true for strictly nocturnal species such as the barn owls Tyto or Tengmalm's owl.[29] With ears set at different places on its skull, an owl is able to determine the direction from which the sound is coming by the minute difference in time that it takes for the sound waves to penetrate the left and right ears.[32] The owl turns its head until the sound reaches both ears at the same time, at which point it is directly facing the source of the sound. This time difference between ears is about 30 microseconds. Behind the ear openings are modified, dense feathers, densely packed to form a facial ruff, which creates an anterior-facing, concave wall that cups the sound into the ear structure.[33] This facial ruff is poorly defined in some species, and prominent, nearly encircling the face, in other species. The facial disk also acts to direct sound into the ears, and a downward-facing, sharply triangular beak minimizes sound reflection away from the face. The shape of the facial disk is adjustable at will to focus sounds more effectively.[29]

The prominences above a great horned owl's head are commonly mistaken as its ears. This is not the case; they are merely feather tufts. The ears are on the sides of the head in the usual location (in two different locations as described above).

Talons

While the auditory and visual capabilities of the owl allow it to locate and pursue its prey, the talons and beak of the owl do the final work. The owl kills its prey using these talons to crush the skull and knead the body.[29] The crushing power of an owl's talons varies according to prey size and type, and by the size of the owl. The burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), a small, partly insectivorous owl, has a release force of only 5 N. The larger barn owl (Tyto alba) needs a force of 30 N to release its prey, and one of the largest owls, the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), needs a force over 130 N to release prey in its talons.[34] An owl's talons, like those of most birds of prey, can seem massive in comparison to the body size outside of flight. The Tasmanian masked owl has some of the proportionally longest talons of any bird of prey; they appear enormous in comparison to the body when fully extended to grasp prey.[35] An owl's claws are sharp and curved. The family Tytonidae has inner and central toes of about equal length, while the family Strigidae has an inner toe that is distinctly shorter than the central one.[34] These different morphologies allow efficiency in capturing prey specific to the different environments they inhabit.

Beak

The beak of the owl is short, curved, and downward-facing, and typically hooked at the tip for gripping and tearing its prey. Once prey is captured, the scissor motion of the top and lower bill is used to tear the tissue and kill. The sharp lower edge of the upper bill works in coordination with the sharp upper edge of the lower bill to deliver this motion. The downward-facing beak allows the owl's field of vision to be clear, as well as directing sound into the ears without deflecting sound waves away from the face.[36]

Camouflage

The coloration of the owl's plumage plays a key role in its ability to sit still and blend into the environment, making it nearly invisible to prey. Owls tend to mimic the coloration and sometimes the texture patterns of their surroundings, the barn owl being an exception. The snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) appears nearly bleach-white in color with a few flecks of black, mimicking their snowy surroundings perfectly, while the speckled brown plumage of the tawny owl (Strix aluco) allows it to lie in wait among the deciduous woodland it prefers for its habitat. Likewise, the mottled wood owl (Strix ocellata) displays shades of brown, tan, and black, making the owl nearly invisible in the surrounding trees, especially from behind. Usually, the only tell-tale sign of a perched owl is its vocalizations or its vividly colored eyes.

Behavior

Most owls are nocturnal, actively hunting their prey in darkness. Several types of owls are crepuscular—active during the twilight hours of dawn and dusk; one example is the pygmy owl (Glaucidium). A few owls are active during the day, also; examples are the burrowing owl (Speotyto cunicularia) and the short-eared owl (Asio flammeus).

Much of the owls' hunting strategy depends on stealth and surprise. Owls have at least two adaptations that aid them in achieving stealth. First, the dull coloration of their feathers can render them almost invisible under certain conditions. Secondly, serrated edges on the leading edge of owls' remiges muffle an owl's wing beats, allowing an owl's flight to be practically silent. Some fish-eating owls, for which silence has no evolutionary advantage, lack this adaptation.

An owl's sharp beak and powerful talons allow it to kill its prey before swallowing it whole (if it is not too big). Scientists studying the diets of owls are helped by their habit of regurgitating the indigestible parts of their prey (such as bones, scales, and fur) in the form of pellets. These "owl pellets" are plentiful and easy to interpret, and are often sold by companies to schools for dissection by students as a lesson in biology and ecology.[37]

Breeding and reproduction

Owl eggs typically have a white color and an almost spherical shape, and range in number from a few to a dozen, depending on species and the particular season; for most, three or four is the more common number. In at least one species, female owls do not mate with the same male for a lifetime. Female burrowing owls commonly travel and find other mates, while the male stays in his territory and mates with other females.[38]

Evolution and systematics

Recent phylogenetic studies place owls within the clade Telluraves, most closely related to the Accipitrimorphae and the Coraciimorphae,[39][40] although the exact placement within Telluraves is disputed.[41][42]

See below cladogram: